In 1991, an EA-6B replacement air group (RAG), included a class called “The 39 Ways to Crash a Prowler.” We reviewed the 39 accidents that had happened since the EA-6B was introduced into the service. Some stories went by quickly, and we learned about engineering fixes and procedure changes to the Prowler. Some mishaps however, were explained in greater detail. One of them was particularly memorable to me.

There was a mishap on the U.S.S. Midway involving an EA-6B that had just returned from a functional check flight (FCF). During the FCF, the electrical (emergency) and hydraulic flaps had been checked out. On the Prowler, the electrical flaps system override the hydraulics for flap operation. In this case, the electrical flaps were inadvertently left in the up position after the check flight. However, the pilot of this flight became more concerned about the fact that no one else was in the pattern when he got to the plane. He thought this might be a great time to do a high-speed overhead break maneuver. He came in for the “$*#!+-hot” break at around 500 mph and started his break on arrival at the ship.

On his downwind leg, the pilot lowered the gear and the flaps, and turned to maneuver for landing, but while he was turning toward final, he didn’t realize the flaps were coming back up. He didn’t have time to notice the electrical flap position was overriding the hydraulic flaps. As he was turning toward final approach, the plane was getting too slow for the flap position. The plane started to stall and started rolling.

The Electronic Counter Measures Officer (ECMO) in the right seat (ECMO1) initiated the ejection. The Prowler has an ejection sequence that puts the pilot out of the airplane 1.2 seconds after ejection is initiated, whether the pilot pulls the ejection handle or ECMO1 pulls it. The back left seat (ECMO3) left instantaneously (“first to go, last to know”), the back right seat (ECMO2) left 0.4 seconds after ECMO3, ECMO1 left 0.8 seconds after initiation, and the pilot went last at 1.2 seconds after the initiation.

This pilot left the airplane as it was 90 degrees to the horizon. His parachute never opened. He skipped along the water like a rock being skipped in a pond. He landed face-down in the water. He had forgotten to buckle up the bottom portion of his SV-2 survival gear, which was designed to place an unconscious victim face-up in the water. Since he had not buckled the bottom of the SV-2, he was left unconscious, face-down. Luckily, the helicopter and rescue swimmers were there quickly and were able to retrieve him from the water. He was rescued and ended up in the infirmary.

After telling us this story, the instructors asked us to make comments about what had happened in the accident and what we thought about the crew decision-making process. Many students had somewhat harsh comments. To our embarrassment, we were told the pilot involved in the incident was in the room with us, and had actually been teaching part of our class for previous days. His name was LT “Buffalo” Bob Smith. Another instructor, in the back of the class, whose callsign was Bozo, said he saw the whole thing happen from the Landing Signals Officer (LSO) platform. He also visited Buffalo in the infirmary. He said they had to do reconstructive surgery on Buffalo’s face, and he was concerned that they didn’t make him any better looking than he was before. Buffalo recovered from the incident and was back on flying status. He was made an instructor in the RAG, and eventually got out of the Navy to work for FedEx.

This was not the only story I heard about Buffalo. When Buffalo was flying the C-9 as a Navy Reservist, he was in Egypt. While he was sitting in the cockpit during preflight, one of the cockpit windows of his C-9 was open because it was so hot. A gust of wind pulled his chart out the window and it started blowing across the airfield. Buffalo chased the chart down the tarmac and into the grass and dirt adjacent to the field. He picked up the chart and showed everybody he got it. The other crew members said, “Buffalo, you’re in the middle of a minefield!” He had to retrace his steps out of the minefield to get back to the airplane.

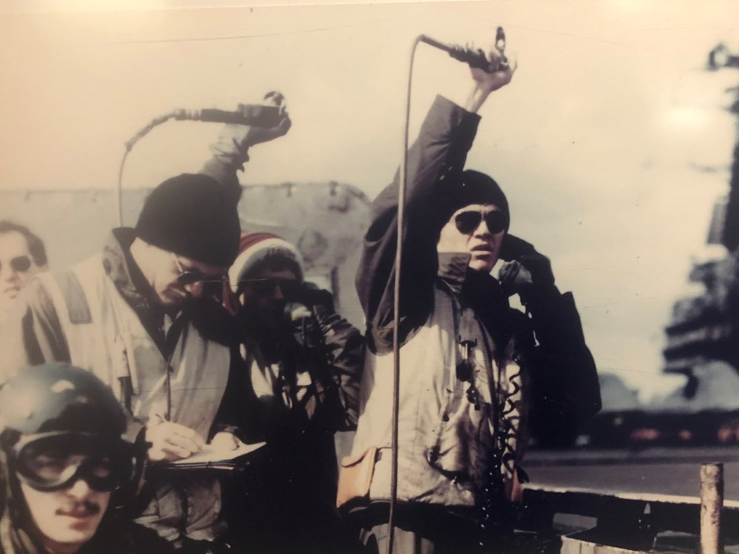

Several years later, I was going through pilot training (I transitioned from NFO to pilot) at Whiting Field, and I noticed a picture of Buffalo on the wall in the building where ground school was held. I wondered if anybody else from the Prowler community knew about this picture. It showed Buffalo standing on an LSO platform wearing a black watch cap. In the picture, he was talking on the radio using an LSO handset. I knew no Prowler pilots ever went through Whiting Field, let alone any NFOs. I had never seen this picture before anywhere else. I forgot about the picture until 2000, when I saw it again hanging in the Smithsonian Institute National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC.

In 2017, Buffalo and I became Facebook friends. I asked him if he knew there was a picture of him hanging in the Smithsonian. He hadn’t seen it. Soon after we became Facebook friends I was in Washington, DC. I visited the Smithsonian and took a photo of that picture. I told Buffalo I had known about that picture for almost 22 years, and that’s probably how long it had been hanging in the Smithsonian.