My father, Col. Henry M. Salley served 30 years in the Army Corps of Engineers. General Hap Arnold personally sent him to England in July 1942 to build airfields and associated billets, depots, hospitals, etc. for the 8th and 9th Army Air Forces. He did not return home until October 1945. He watched the first bombing raid over Europe take off and the last raid to return. By the end of WW-II in Europe, he was responsible for the repair and maintenance of over 80 airfields. Pilots helped win the war, but couldn’t have done it without the Corps of Engineers.

A year ago, I got around to reading all the letters between my mother and father during WW-II. My mother’s letters were lengthy, but my father’s were short because of censoring and V-Mail limitations. In one of the V-Mails he mentioned that he had survived a bad experience which he would tell her about after the war was over. In a later letter, he explained the situation. Turns out it involved D-Day.

Below is an extract from Col. Salley’s letter to my mother about his D-Day experience:

2 July 1945

HQS U.K. Base Section, ETO

Engineer Service

APO 413, Postmaster, New York, NY

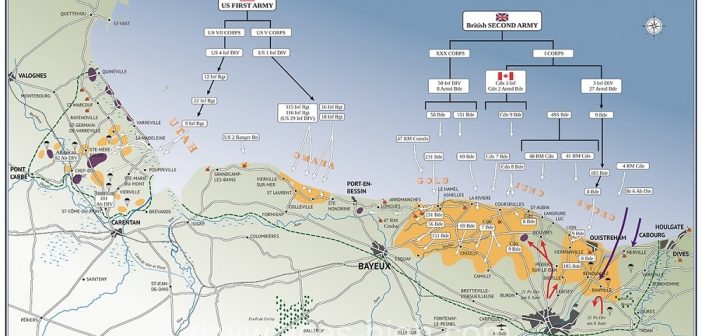

“In addition to my other jobs, I had the responsibility of “Mounting” the airborne (glider) and parachute troops in my district for the Normandy landings. They were to be flown from a large number of Airfields in my District. By “Mounting” was meant preplanning all facilities for their housing and messing for the period they were moved onto the fields until they left. This meant a lot of work, as several thousand extra men had to be cared for several days on each field. Our airfields were not built to care for so many people. I used Engineer troops to set up temporary camps, messes, sanitary facilities, water supply, etc, and do all the housekeeping as well, and also to build enclosures around the camps and let no one in or out who had previously not been “briefed.” And all this had to be done quickly so as not to draw attention to something unusual going on.

This “Mounting” part was easy, but when they also gave me the job of distributing the operational maps to the same people, I balked as I did not think I should be given that responsibility. It meant that I had the secrets of the invasion in my hands several days in advance, and I had enough to worry about already. Anyway, I got the job whether I wanted it or not, and set up the organization to handle it.

It was handled with precautions taken to insure, that units were not given the wrong maps and sent somewhere else, and other security measures taken. All of this took just hard work and planning. We were all set. Maps were ready for distribution. We knew D-Day had to be within certain defined interval, but not the day or hour as that depended on weather conditions, etc. These maps could not be delivered too early, but just in time for the people who would use them to study and be “briefed” on what they were to do. Of course, the people who got the maps were “sealed in” their airfields and camps, until the mission left.”

Word was to come to me in code when to start delivery of maps. Everything was set and ready. We knew the invasion had to come soon or be postponed. That night I was tired out and went to bed, but at eleven o’clock I was awakened by the officer-of-the-day and the signal officer who said: “Maybe you can tell us what this teletype means”. The teletype was from the airborne Army Headquarters and said: “For God’s sake, who knows anything about Map Distribution” and had been sent to about everyone in England in the clear. Then I found out that the signal officer at our Headquarters received a message addressed to me in a code the code clerk could not decipher, at eleven o’clock that morning. Without saying anything to me, he had sent the message to London to be decoded, before delivery to me. That meant twelve hours delay since the Army were apparently asking for their maps. That delay could have been vital, and I was pretty sick about it.

My map distribution depot was 75 miles away and it took some little time to get a message through to them, and it was with some relief when my officer there, Maj. Bothsford, said he had started delivering maps at noon. Of course, he talked to me in a code we had arranged. We had foreseen that some misstep like this could happen and we had arranged for the Army to send an intelligence officer, who was known to my officers, to the map depot to let them know when to start if other communication failed. When the Army couldn’t reach me, they sent their man down and everything was all right. My man couldn’t let me know, as they were too busy and thought I knew about it anyway.

The men who were to get the maps were getting them all right, but the higher headquarters didn’t know it, so they were trying to reach anybody they could to help them find their maps. It was a grand mix up and maybe looks a little funny from this distance, but it was no joking matter that night. Every map was delivered ant things came off fine. It was a grand job on the part of my officers at the depot. I recommended them for the Bronze Star Medal, but they haven’t gotten them yet. I have not given up hope for them as a lot of good cooks and mess officers have been given them since.

I also “Mounted” the airborne troops for the Arnhem show too and that was easy the second time. It was quite an experience to walk down the large line of planes waiting to take off, and talk to the parachutists and feel their tension, then see them climb into their transports and take off and know that many will be dead in a few hours. I watched one hundred planes leave on one field, filled with parachutists one morning, then drove a few miles to another field and watched the glider echelons leave. They were all scared to death, but surprising confident in themselves.

Extracted by Hammond M. Salley, US Army, Infantry, (Ret) – 4/10/2020