At their April, 2024 meeting, the members and guests of the Grampaw Pettibone Squadron were privileged to be visited by Dr. Dirk H. deDoes, Major, USAF(Ret). Dirk received his Ph.D. in aerospace engineering from USC in 1969. He has over 55 years in developing and evaluating military and civilian aerospace systems. In concert with co-workers, he authored and presented over a dozen technical papers on Global Positioning System (GPS), and aircraft and missile guidance and control. At our April meeting our speaker shared his research and documentation of the history involving WWII Russian female combat pilots and specifically those known as the “Night Witches”.

Dirk began his presentation by setting the events that led to the Soviet Union entry into World War II. Joseph Stalin came to power in 1924, following the death of Vladimir Lenin. As a result of Stalin’s leadership decisions in farming and produce selection, millions died of starvation in the Ukraine between 1932-1933. Stalin did not trust senior members of the government nor did he tolerate any disagreement with his decisions within the country. During the period 1936-1938, it is estimated that up to 1.3 million members of the leadership in the government, business and military were shot, imprisoned or deported. This became known as Stalin’s Great Purge. This loss of leadership had a disastrous effect on the military.

In spite of ideological differences between Germany and the Soviet Union, the two countries signed a non-aggression pact in August 1939. It ushered in a period of military co-operation which allowed Hitler to ignore western diplomatic moves and invade Poland. The non-aggression pact only held until June 1941 when Germany invaded the Soviet Union.

In their invasion, known as Operation Barbarossa, the German military was able to advance hundreds of miles into Soviet territory in a very short time. Poor planning and lack of organization by the Soviets, allowed the Luftwaffe to destroy 4,000 Soviet planes within the first week. Hundreds of thousands of Soviet soldiers were captured and many perished. The loss of tens of thousands of weapons captured or destroyed, further limited the Soviet Union ability to defend itself. By November 1941 most of the Soviet air force was destroyed, and the German army was closing on Moscow & Leningrad.

As a result of the high casualty losses suffered by the Soviet military, Stalin approved the replacement of men in second lines of defense positions by women. He granted women roles such as anti-aircraft gun crews, combat nursing, flight instruction and combat air traffic control for example. These provided opportunities and openings through which qualified women could ultimately become involved in combat.

Aviation, as both a hobby and career for women, began to increase in popularity as early as the 1920s and 1930s. Women took advantage of the opportunity and trained along side men in aviation and aircraft servicing at local airports and aviation clubs. Women acquired skills in a variety of aviation events: powered flight, glider pilots, navigators, parachute instructors and mechanics.

One of the earliest female pilots to achieve recognition in the Soviet Union was Marina Raskova. Her accomplishments in the 1930s as both a pilot and navigator, led to her being referred to as the Russian Amelia Earhart. Marina joined the Soviet air force in 1933 and shortly after joining become the first woman to become a navigator in the Soviet air force. As her achievements as a pilot and navigator progressed, by 1941 she was promoted to Major in the air force.

Marina Raskova

Major Raskova began fighting for the creation of women’s military aviation units from the day the Germans invaded Russia in June 1941. Because of Major Raskova’s reputation, experience and her personal connections with Stalin, in September 1941, she was granted permission to form the 122nd Composite Air Group. Over 1000 girls and young women, ranging in age from 17 to 26, were reorganized into the 586th Fighter Aviation Regiment, the 587th Day Bomber Aviation Regiment and the all women 588th Night Bomber Aviation Regiment. Each regiment was to include female aircrews, ground crews, and support staff. Major Raskova put out a call for volunteers both experienced women who learned to fly in the 1930s and those with little or no experience.

Training for women was more challenging than men. In addition to being trained for only six months, compared to the normally required three years of training for men, the women were subjected to physical, as well as sexual harassment from male pilots and crews. Women were also expected to complete military training that included drilling and marching. Attaining the skills needed to fly military aircraft were compounded by the fact that very few planes were dual control, which required up to 14 hours/day of both classroom and flight training. Approximately 25% of the Soviet Air Force were women.

Training bases were limited in offering comfortable conditions and services. Daily meals were typically comprised only one/day of soup and black bread. Housing could be in a barn, a cow shed or other make-shift conditions. Typically, no electricity, running water or suitable sanitary arrangements existed.

The assignment of women to the newly created units were based on their performance during training. According to Dirk’s research, in spite of the conditions and personal obstacles, three air regiments were created. The 588th was commanded by Major Yevdokia Bershanskaya, a skilled pilot with 10 years flying experience. The regiment included 400 women divided into three squadrons with 10-15 aircraft per squadron. The women suffered during training due to their gender. In addition to poor accommodations and old equipment, the women had to wear hand-me down men’s uniforms too large for most of the unit members. Sexual harassment and abuse from other units added to the challenge.

The aircraft that they trained in and flew on missions, was an additional obstacle to overcome. The regiment was initially equipped with the Polikarpov U-2, later designated PO-2. It was a single engine open cockpit trainer, used as a light bomber and flown by a pilot and gunner/observer. Due to its wood and fabric construction, it was a challenge to fly in the winter. However, it had the advantage of being difficult to identify in flight by the Luftwaffe using their early style radar. But with a top speed of only 98 mph, it was an easy target to locate by enemy search lights and to destroy if hit by enemy anti-aircraft fire. The slow speed was an advantage against enemy aircraft by making it difficult to be shot down by enemy fighters. The cruise speed was around 68 mph, slower than the stall speed of the German Messerschmitt Bf-109, at 75 mph.

Polikarpov PO-2

Dirk described the unit mission requirements as being very challenging. Each plane could only carry a maximum bomb load of 770 pounds. This required the unit to fly multiple night missions, when attacking enemy bases. A nightly mission to destroy the enemy base may require as many as 15 flights for a total of 10 hours per plane and crew. A typical pilot in the 588th flew 800 missions during the war. Together, the regiment flew more than 24,000 combat missions, with the most occurring on December 22, 1944. On that night alone, they flew 324 bombing runs.

Most missions were flown low to the ground and nightly attacks were a constant reminder for the enemy to stay awake. The pilots would throttle their engine back to idle before reaching the target and glide towards the ground to release their bombs. After releasing their bombs, they would throttle up their engines and return to their base to rearm for their next nightly mission. In one mission, after running out of bombs, they carried railroad ties and dropped them on the enemy bases they were attacking.

The sound of the wind over the wings of the plane was often times described as the swishing sound of a broom. The enemy began to refer to the attackers as Nachthexen, “Night Witches.” The success of the unit led to it being the most highly decorated female unit in the Soviet Air Force. Operating from October 8, 1941 to May 4, 1945, 30 pilots died, 23 members received the title Hero of the Soviet Union, five posthumously, two were eventually declared Heroes of Russia and one was awarded Hero of Kazakhstan.

Dirk introduced the second regiment that was initially commanded by Major Marina Raskova. The 587th Light Bomber Regiment which became operational on December 25, 1942, was equipped with the Petlyakov PE-2 Light Bomber. This was a twin-engine aircraft also used as a heavy fighter, horizontal bomber as well as a dive bomber. It was regarded as the one of the outstanding tactical aircraft of the war with over 11,430 built and representing 75% of the Soviet twin-engine bomber force.

Petlyakov PE-2

Vladimir Petlyakov was credited with the design of the aircraft and although regarded as an excellent engineer and designer, he was arrested during the period known as the Great Purge. During his time in prison, he designed the aircraft that later became known as the PE-2.

The women who joined the regiment, were among the best, and were personally selected by Major Raskova. Unfortunately, during its first assignment, two squadrons encountered a heavy snowstorm. One of the planes piloted by Major Raskova crashed, and as a result of her injuries, she died on January 4, 1943.

The regiment continued to operate with new leadership, and the women learned how to operate the aircraft they were assigned. Because of the size of the plane, the crew were forced to make adjustments in order to operate the aircraft. Rudder pedal blocks and seat cushions were added in order for the crew to reach the controls. When taking off the aircraft, the navigator assisted the pilot in controlling the plane. In spite of the challenges faced by the women, the regiment had a successful operation, completing 1,134 combat missions during the war with five female pilots receiving the title of Hero of the Soviet Union.

The last unit described by Dirk was the 586th Fighter Aviation Regiment. The unit was initially equipped with the Yakovlev Yak-1 fighter. The regiment was upgraded with newer models, the Yak-7 and finally Yak-9.

The unit had very high standards and it was hard for women to join. Twenty-five were accepted after graduating from the Yak-1 flight course in December 1941.

Yakovlev Yak-1

The regiment flew 2,073 combat sorties, fought directly in 125 air battles and credited with shooting down 25 enemy aircraft. These achievements, according to Dirk’s presentation, was in spite of the equipment, infrastructure, training and experience which was inferior to the German’s operation. Initial fighter tactics were disasters and many planes were lost. Once missions were switched to hunting in pairs and attacking targets of opportunity, the performance improved significantly.

Two members of the unit became aces. Lydia Litvyak, 21 and Yekaterina Budanova, were posthumously awarded the titles Hero of the Soviet Union and Hero of the Russian Federation respectively.

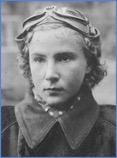

Lydia Litvya

Yekaterina Budanova

Dirk’s research indicates that Lydia Litvyak was recognized as a double ace and was known as the “White Rose of Stalingrad”, due to her carrying flowers when she flew. Yekaterina Budanova was credited with 266 combat sorties, 6 enemy aircraft destroyed with an additional 5 shared in shoot downs.

The squadron wishes to thank Dr. deDoes for his informative and entertaining presentation and looks forward to future topics of interest for our audience.

Tim Brown, President of GPSANA, Dr Dirk DeDoes, Presenter, David Malmad, Public Affairs Officer GPSANA