At the monthly Grampaw Pettibone Squadron virtual meeting, Marc Liebman, Captain, US Navy (ret) was the guest speaker. He spoke about his experience as a Naval Aviator during Desert Shield and Desert Storm.

Marc started his presentation noting that until 1973, every Student Naval Aviator had to carrier qualify during the Basic Phase of flight training. He, like all Naval Aviators, started flying in the T-34B and then the T-28B/C and made seven arrested landings on the U.S.S. Lexington. After carrier qualification, he was assigned to fly helicopters in the fleet. He noted that his military career covered three decades, eight presidents and three shooting wars. In his talk, Marc addressed the many missions that the Navy assigned to the SH-60.

Marc’s presentation focused on the U.S. Navy circa 1991. Marc was deployed to the Gulf and joined a group called Battle Force Zulu. Within Battle Force Zulu there were warfare designees. The officer in charge of power projection could be either a flag-officer or an Air Wing Commander and was known as Zulu Papa. The senior cruiser captain and in-charge of anti-air warfare was called Zulu Alpha and Zulu Sierra for anti-surface warfare

Zulu Lima reports to Zulu Sierra, which was one of the reasons our speaker was on the U.S.S. Ranger. Zulu Lima was responsible for controlling all 140+ operational tasking perspective and mission helicopters from 14 nations that were members of Battle Force Zulu along with SEALs not assigned to Central Command. In referring to the slides during his presentation, Marc identified a typical list of missions assigned to the helicopter.

Not all the countries followed the same rules of engagement (ROE) that the United States or the Coalition of Forces put forth. For example, the Canadians were not allowed to engage in combat operations unless a Canadian asset was threatened. Therefore, their frigates would be sent as far North in the Gulf as possible so that they could request air support if threatened. This tactic enabled their F/A-18s to fly CAP over the Canadian ships and enabled the U.S. Navy aircraft to refuel from Canadian 707 tankers. In the first 6 to 7 days of the war, the United States Navy obtained more fuel for their aircraft from British, French and Canadian tankers then they did from U.S. Air Force tankers.

Marc described a variety of helicopters used by the Coalition forces in the Gulf. The H-3 was flown by the military of USA, UK, Canada and Australians. The U.S. military were the only member of the Coalition using SH60 helicopters. In addition, Battle Force Zulu had Task Force 160 detachment flying OH6s. The nations flew Sea Lynx’s, French Gazelles and Bell 212s. He was able to fly with other Coalition members. When the ships arrived, Marc asked allied aircrews three questions:

“What can you really do?”

“What can’t you do?”

“What is your government going to prohibit you from doing?”

Marc stated that the operators were fully on board and were going to do pretty much what they were asked to do and would stretch their country’s restrictions. What we did was adapt their tasking to their ROE restrictions because shipping surveillance was a huge part of the Zulu Lima mission, particularly in the Northern part of the Arabian Gulf.

Showing a picture, Marc described the geography of the Gulf. Iranians or Persians on the northern shore referred to the waters as the Persian Gulf. At any one-time during Desert Shield, there were 5,000 ships -Allied, neutral, enemy – as well as hundreds of oil platforms of all types. Some were large oil platforms used to load tankers, others were drilling rigs, or caps to dormant or played out wells.

Arab nations on the southern shore refer to the body of water as the Arabian Gulf. In a comparison Marc noted, the naming of the waters was not as bad as operating with the Koreans and the East Sea and the West Sea. The East Sea is the Sea of Japan and the West Sea is the Yellow Sea. When he retired in 1993, if one uses the Sea of Japan or the Yellow Sea when briefing a South Korean officer, he will reject your information until you correct the terminology. When talking to the local the Gulf Cooperation Council Navies, they preferred we use the words Arabian Gulf rather than Persian Gulf.

At the beginning of the war, on January 16, 1991, the U.S. had three carriers in the Arabian Gulf. They were located primary north of Abu Dhabi. The peninsula where Qatar and Bahrain are located are referred to as the “thumb”. When the war ended towards the end of February, the carriers were north of Bahrain and Qatar.

Because of the volume of traffic, missions of Zulu Sierra flying S-3s and the P-3s were challenged to keep track of all the ships in the gulf. E-2s helped maintain an overall picture and direct the S-3s and P-3s to were look at each ship as often as possible. The carriers maintained an E-2s in three orbits – one in the northern gulf off Kuwait, another in the central gulf off Abu Dhabi and one near the Straits of Hormuz. The E-2s were kept busy supporting Air Force E-3s and when the data links worked, the two aircraft could provide an integrated air picture from Bagdad to the Straits of Hormuz. The Air Force was having issues with them coming in to support strikes. The E2s were used to queuing in for Command and Control and separation. Mark remarked that in his role as Zulu Lima, he considered the E2s as non-players in a combat role.

The Air Force wanted every sortie on the Air Tasking Order which was 900+ pages long during Desert Storm. This was impractical because much of Zulu Lima’s tasking was dictated by what the Iraqi Navy and special forces did. We could not submit targets 48 to 72 hours in advance. The agreement was that the Navy helos would stay below 3,000 feet.

The SH-3Hs assigned to the Navy HS squadrons were old and tired. To extend blade life, they were initially restricted to a maximum of 90 knots! This as routinely ignored.

When Marc first arrived, he requested the reserve HH-60Hs to support Navy SEALS and to provide combat search and rescue assets. Initially, there was resistance within the Navy command structure to have Naval Air Reserve squadrons participate in Desert Shield and Storm.

Initially, M60 machine guns were mounted on the SH-3Hs and were called Combat SAR helicopters. Marc commented that this reminded him of 1966, off the coast of Vietnam, when the service did exactly the same thing. Thankfully, cooler heads prevailed and the HH-60Hs were deployed and played a major role in inserting U.S. and Allied Special Forces during what was known as the “Great Scud Hunt” in Western Iraq.

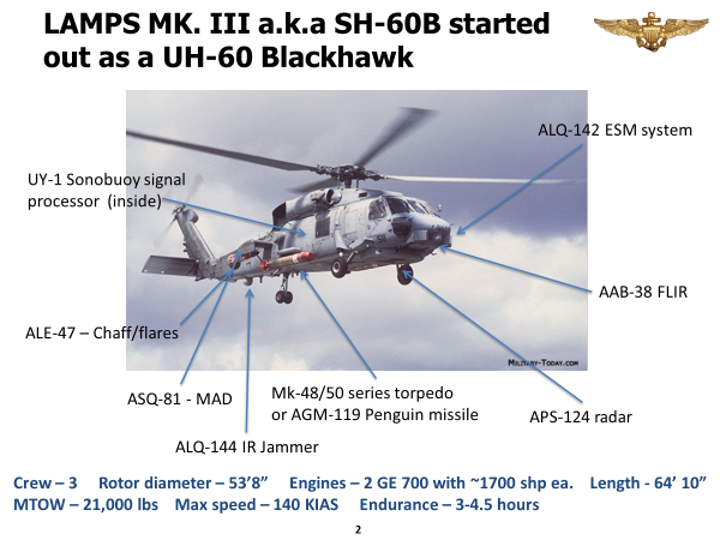

The primary Navy anti-shipping assets were the early model SH-60Bs with an ESM system, good search radar – APS-124, radar jammer. Although they could carry sonobuoys and torpedoes, none were carried because the Iraqis did not have any submarines. Our ROE would not allow us to use the Penguin (AGM-119) anti-ship missile because it would seek out the largest radar or IR target. We couldn’t risk hitting a neutral or friendly ship so the Penguins stayed in their boxes. This left the U.S. Navy helicopter community in the region weaponless, except for the M-60s.

According to Marc, the SH-60 was far more maneuverable then anything he had previously flown. The aircraft was ballistically tolerant with lots of power, no over-torque problem, fast, could land in high winds and supposedly very crashworthy. However, it does not float.

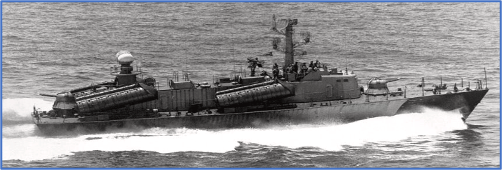

The primary naval threat to Battle Force Zulu were the Iraqi Osa class ships (patrol, guided missile or PGMs) armed with four Styx missiles and a 30mm radar-controlled gun. It was believed that the Iraqis had 17 boats and planned to use oil platforms to hide them so they could sprint out at 35 knots and launch the missiles at coalition forces. The second task was to prevent Iraqi Commandos from coming out of the Shatt-Al-Arab waterway and conducting raids in Saudi Arabia. The Air Force tried using AC-130s to interdict the Commando force without success.

A recommendation was made to use the H-60s as an AWACS platform and vector the Sea Lynx with Sea Skua missiles firing position three to five miles from the Iraqi PGMs. A test was set up and within a few hours a working procedure was established. The idea was to launch the H-60s as mini-AWACS to locate the Osas and guide the Royal Navy Sea Lynxes to a firing position. This was accepted by the Air Force as long as the helos remained below 3000 feet.

The tactic that evolved was well within the ROE and also solved the problem of finding slow moving ships amongst the oil platforms. The SH-60B would uses its radar to vector the Sea Lynx to a point where its target acquisition radar detected the ship. The Sea Skua is a command, line of sight missile that follows a radar beam from the helicopter to the target. Its maximum range is about 15 miles, but to ensure accuracy and minimize the time of flight of the sub-sonic missile, the Sea Skuas closed to within seven to eight miles before firing. This also kept the Sea Lynxes out of range of the Osa’s 30mm gun. When the Sea Skua was launched, the helicopter was between 100 and 200 feet.

To target the PGMS or other Iraqi ships, the H-60s would launch either from a Spruance Class Destroyer or Aegis Class Cruiser, and go hunting in the northern part of the Arabian Gulf. Once the target ship was detected, the Lynx would be vectored to fire on the target. A total of 12 boats were knocked out within a three-night period. The process was simple and effective and the threat went away.

The same process was performed with the Zodiacs and High-Speed Cigarette Boats. One night when the Lynx was not available, an F-14 in the area was called in and firing a Sparrow missile, destroyed the target. Marc indicated that after a two to three-week period during which Iraqi’s boats full of commandos kept being sunk, the Iraqis stopped sending them south.

Once the threat from the missile boats were removed, the Allies needed to gain control of the Iraqi oil rigs. Some were ignored while others were either taken out or bombed. The rigs that had Triple A or guided missiles, were suppressed first. Some had to be physically assaulted. That was when Task Force 160 and SEALs were used.

Fear of an environmental disaster was the second reason a rig had to be taken. On some rigs, we debated if we could get control of the rig before the Iraqis opened the valves to dump crude into the gulf. Central command decided that except in three or four cases not to attack the rigs. Those that were attacked, were taken quickly with few, if any Allied casualties.

Marc told several “war stories.” The first was about Qurah Island which had been taken over by the Iraqis. The island which is ~900 feet long and ~600 feet wide and is off the coast of Kuwait. The island had an early warning radar site and was being equipped with surface to air missiles. One night, two OH-6s were scouting out the island for targets when, an Iraqi officer on the ground was seen to be waving a white sheet. One OH-6 landed and the helo observer walked up to the Iraqi, who wanted to surrender along with the 120 soldiers on the island. The instructions given to the Iraqi, were to shut off the radar and stop shooting at any aircraft flying in the vicinity. The Iraqi was not told that Kuwaiti Marines were going assault the island in two days. When the Kuwaiti Marines stormed ashore, they were met by 120 Iraqi personnel lined up in parade formation with a big white flag. This is the true story about how the first piece of Kuwaiti territory was taken back.

The next story also never made the papers: Vice Admiral Arthur wanted to know how many combat vets were in the Persian Gulf Battle Force and the ones in the Red Sea. A request was sent out and between the five carrier battle groups, there were 18 combat vets from the Vietnam War and, Marc was the only helo driver. The vets talked to the air wing squadrons about what it was like to fly in combat. Iraq’s defenses would be the first integrated air defense system U.S. forces had attacked since Vietnam. When Marc walked into the ready room of the HS squadron on board the U.S.S. Ranger, he asked a Navy Lieutenant JG who, looked as if he were 12 years old. “Lieutenant, where did you get your wings?” The JG said with a big smile, “Sir, I bought them at Sears and Roebuck.”

Marc was 47 at the time and felt that he was sending into combat those young enough to be his children. When Desert Storm began, his son just turned 13 and his daughter was 17.

Next, Marc described images that were seen on the news where oil wells were burning in Kuwait and a horrible black cloud hung in the sky, blotting out the sun. The wells spewed an oily gritty smoke into the air. The smoke which smelled of burnt sulfur would ablate the leading edge of propeller, turbine and rotor blades. It wore off the paint on the noses of aircraft and coated the aircraft with a greasy, oily, gritty scum. Flying through rain didn’t help either because the mix would turn acidic. The aircraft on the Ranger had to be washed down frequently to remove the coating. The other by-product of the burning oil wells was hydrogen sulfide gas.

On the second day of the well fires, the wind blew the smoke over many of the ships in the Gulf setting off the chemical attack alarms. On Ranger, we donned our MOPP gear. Normally, putting on the suit, – head covering, jacket, pants, boots and gloves – should take about four minutes. Marc stated that as soon as the alarm sounded, he was sure he was dressed in two minutes. Everyone on Ranger in the protective clothing for about 45 minutes before it was determined that we were not being attacked by mustard gas.

When the war ended, there were four carriers – Midway, Ranger, America and Roosevelt in the gulf. The COs of the four ships agreed to a drag race. Each of the ships had a full complement of aircraft onboard. The USS Midway with upgrades since first launched in 1945, was about 64,000 tons. Ranger, weighed 80,000 tons; the America displaced 83,000 tons and the nuclear-powered Roosevelt was the biggest at 117,000 tons. The first ship to 10 knots was Midway, and the first ship to 15 knots was Ranger. By the time the race reached 20 knots, Ranger was well ahead of everyone else and America, was way in the back. Roosevelt passed Ranger at about 25 knots as if it were standing still. The Captain of the Roosevelt broadcast on the common frequency with the other ships participating and announced that he would shut the power down when the ship passed 40 knots.

One day after the war, Royal Air Force Tornadoes did a fly-by of the Ranger. The ship provided electronic warfare support for the aircraft during the first few days of the war. The two-plane element was in a 90-degree angle of bank as it passed the ship. Marc indicated that someplace he had photo he took of a Tornado while it went by at 400 knots below the flight deck.

Marc compared the technology of the period and the reception upon returning home between the Gulf War and his earlier experience in Vietnam. Instead of sending cassette tape letters, he could make cell phone calls from the ship. Arriving home, he was treated to a ticker-tape parade instead of being spit on, having car tires slashed, being told not to wear his uniform off base or mention he was in the military during any conversation with civilians.