At their October 14, 2021 meeting, Grampaw Pettibone Squadron hosted an in-person presentation featuring Captain Marc Liebman US Navy (Ret). Captain Liebman shared his experience as a Naval Aviator. He served thirteen years on active duty, and thirteen years in the reserves, retiring in 1993. He has flown as pilot-in-command both fixed and rotary-wing aircraft. He has over 3800 Navy flight hours and five commanding officer assignments. He considered his military career to be incredibly successful, particularly since he did not serve any time in the Pentagon.

In his presentation Marc described events that had occurred while directing over 140 helicopters from 14 coalition nations during Operation Desert Shield and Desert Storm beginning in January 1991. When told he was going to be Zulu Lima and responsible for command and control of the Arabian Gulf Battle Force’s helicopters, he asked about the instruction on his duties. The answer was a fax of a two-page instruction which had the command relationships and instructions to “go figure it out.”

Showing a picture of the region where operations occurred, Marc described the geography of the Gulf, where most of the military activity took place supporting Kuwait. Living in Iran, one will refer to the waters as the Persian Gulf; from Riyadh, Dubai or Kuwait City, it is the Arabian Gulf. The local Gulf Cooperation Council Navies, preferred we use the words Arabian Gulf rather than Persian Gulf.

At any one-time during Desert Shield, there were 5,000 ships, allied, neutral or enemy, and hundreds of oil platforms of all types. Some were large oil platforms used to load tankers, others were drilling rigs, or caps to dormant or played out wells. The gritty air covered everything. Clothes and surfaces were dusty, and the food was sandy. Aircraft were in constant need of service as the blowing sand stripped paint, and damaged aircraft blades and moving parts.

For his assignment, Marc reported to a Rear Admiral, who reported to a Vice Admiral, who reported to the Commander of CENTCOM (Central Command), General Schwartzkopf. The staff of the Air Component Commander (General Horner) insisted that all helicopter operations in the Arabian Gulf were included in the Air Tasking Order (ATO). Missions on the ATO had to be submitted approximately 72 hours in advance. The “ad hoc” nature of many helo operations made this impractical. As a compromise, it was decided that as long as the helos stayed below 3,000 feet, Zulu Lima would provide a summary of its operations on a daily basis so the ACC could track the sortie count as well as the type of missions flown. Another issue were the different rules of engagement imposed by some of the countries whose helicopters were tasked by Zulu Lima. Complying with United Nations Command, United States Command and the commands from individual nations added a level of complexity to the role Marc was carrying out.

Marc was responsible for tasking and operational control of all helicopter operations assigned to Battle Force Zulu, in the Arabian Gulf. The helicopter missions included CSAR, special operations, logistics, shipping surveillance, counter smuggling, personal transfer, photography and more. His staff were reservists-two O-5s, two O-3s, three E-6s and four E-5s.

Before hostilities started, Marc visited each helicopter detachment and flew. There was little consistency in the sensor suites or weapons carried by the helicopters. For example, the Italian and Spanish Bell 212 were designed to carried anti-submarine torpedoes and were not equipped with a FLIR. They did have a radar and were tasked to conduct shipping surveillance. French flight crews operating the Gazelle, and did not have any armament. They were given shipping surveillance and logistics missions. The Australian SH-2Gs which had an excellent radar were shipping surveillance missions.

At the beginning of the war, on January 16, 1991, the U.S. had three aircraft carriers in the Arabian Gulf operating north of Abu Dhabi. When the war ended in late February, the carriers were north of Bahrain and Qatar. In some missions aircraft were in the air less than 20 minutes from launch to recovery. The aircraft complement onboard the USS Ranger carried an all-Grumman air wing. F-14s, A-6s, E-2s and S-3s.

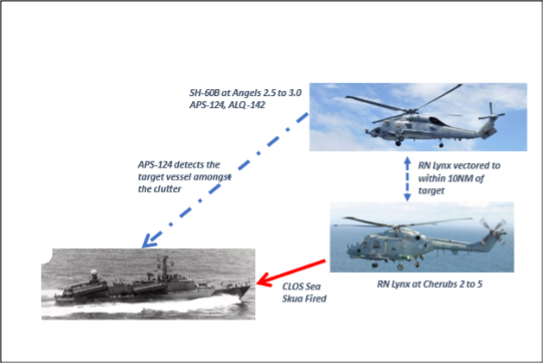

Of the helicopters flown by the U.S. Navy, the SH-60B was the most versatile. Known as LAMPS (Light Airborne Multi-Purpose System), the SH-60B was the result of a United States Navy’s program to develop helicopters that could fly in anti-submarine and anti-surface warfare missions. The primary purpose of LAMPS was to scout outside the limits of a fleet’s radar and sonar range to detect and track enemy submarines or missile-equipped escort ships and feed the real-time data back to their LAMPS mothership. Although they could carry sonobuoys and torpedoes, none were carried because the Iraqis did not have any submarines. The SH-60B could also be equipped with AGM-119 Penguin anti-ship missile. However, the ROE would not allow the use of the Penguin because it would seek out the largest radar or IR target. This would put any large coalition or neutral ship at risk. Flying between 1000-2000 feet above the water, the SH-60B was capable of picking up targets out to 50 miles. Maximum speed was 140 knots with a 3-4.5 hour.

In the beginning of the war, Zulu Lima was tasked to eliminate the Iraqi Navy. The Iraqis were equipped with 16 OSA PGM (Patrol Guided Missile) ships. The craft were over 100 feet long, 40 knot top speed and equipped with 30mm cannon and anti-ship missiles. The ships could hide among the oil platforms to ambush the coalition ships.

Carrier Group Seven staff, its embarked SH-60B detachments and Marc discussed how best to sink the Iraqi Osa PGMs. Using the SH-60B’s APS-124 radar, the aircrewman could function as a mini-AWACS. To attack the Iraqi ships, the Royal Navy’s Lynx helicopter, equipped with the Sea Skua missile were guided into firing position, 5 – 7 miles from the Iraqi vessel. In three nights, the SH-60B/Sea Lynx hunter killer team took out 12 Iraqi PGMs ships.

A second mission was to target Iraqi cigarette boats conducting commando raids. After an earlier US Air Force mission flying C-130s were unsuccessful in locating and removing the targets, the same Hunter/Killer helicopter team was utilized and two targets were located and eliminated.

Marc described events surrounding the mission to secure Kuwati territory, Qurah Island which is 20 miles off the coast. It was taken by the Iraqis and was firing on U.S. ships and aircraft. After an air attack by A_6 aircraft, U.S. surface ships fired on the island. This was followed by a SEAL team that assaulted and captured the island. Two days later, forces from Kuwait “invaded” the island and took the Iraqis prisoner.

To turn the HS squadrons into combat SAR units, M60 machine guns were mounted on the SH-3Hs. This is exactly what was done during the early days in Vietnam. Thankfully, cooler heads prevailed and the HH-60Hs were deployed and played a major role in inserting U.S. and Allied Special Forces during what was known as the “Great Scud Hunt” in Western Iraq.

When news stories were broadcast regarding the oil fires, they could not fully convey the impact to forces in the region. A horrible black cloud hung in the sky, blotting out the sun. The wells spewed an oily, gritty smoke into the air. The sand and the grit in the smoke which smelled of burnt sulfur would remove material from the leading edge of propellers, turbine and rotor blades. It wore off the paint on the noses of aircraft and coated the aircraft with a greasy, oily, gritty scum. Flying through rain didn’t help either because the mix would turn acidic. The aircraft on the Ranger had to be washed down frequently to remove the coating.

The oil well fires started by Iraq created significant environmental challenges and risks. On the day after the wells were set on fire, the wind blew the smoke over many of the ships in the Gulf setting off the chemical attack alarms.

On Ranger, personnel donned their MOPP gear. Normally, putting on the suit (head covering, jacket, pants, boots and gloves), should take about four minutes. According to Marc, he was dressed in two minutes. Everyone on Ranger was in the protective clothing for about 45 minutes before it was determined that they were not being attacked by mustard gas.

When the war ended, there were four carriers – Midway, Ranger, America and Roosevelt in the Gulf. The COs of the four ships agreed to a drag race. Each of the ships had a full complement of aircraft onboard. The USS Midway with upgrades since first launched in 1945, was about 64,000 tons. Ranger, weighed about 80,000 tons; the America displaced 83,000 tons and the nuclear-powered Roosevelt was the biggest at 117,000 tons. The first ship to achieve 10 knots was Midway, and the first ship to make 15 knots was Ranger. By the time the race reached 20 knots, Ranger was well ahead of everyone else and America was way in the back. Roosevelt passed Ranger at about 25 knots as if it were standing still. The Captain of the Roosevelt broadcast on the common frequency with the other ships participating and announced that he would reduce speed when the ship passed 50 knots.

At the end of his presentation, Marc compared the technology to communicate with loved ones back home and attitude between the Gulf War and his earlier experience in Vietnam. Instead of sending cassette tape letters, he could make cell phone calls from the ship. Arriving home, he was treated to a ticker-tape parade instead of being spit on, having his car tires slashed, being told not to wear his uniform off base or mention he was in the military during any conversation with civilians.