At the October 29, 2020 Grampaw Pettibone Squadron virtual meeting, author John G. Lambert was the guest speaker. He described the history of the USS Independence, CVL-22, aircraft carrier, from being conceived, her construction, to its war time experience, post-war and end. The presentation was based on his well-researched, 872-page book, compiled over a 9-year period, at the request of the ship’s Reunion Group.

In 2008/9, the USS Independence Ship’s Reunion Group asked John Lambert to begin an intensive research on the history of the ship. The study included interviews with aviators, crew members and attendance at reunion events. Additionally, travels to NARA (National Archive and Records Administration), both College Park, MD & San Bruno, CA locations, a library in Camden, NJ where some NYSB records are archived, and NAM (Naval Aviation Museum) Pensacola supported his research.

Beginning the war with only seven aircraft carriers in December 1941, the U.S. inventory was reduced to three by years end in 1942. The USS Independence was an expedient of war, having begun its life as the Cleveland Class Light Cruiser – USS Amsterdam (CVL-59), still under construction, almost to her main deck. Development and construction of the then new large sophisticated Essex class carriers, was projected to take far too long to build. The nation was in dire need to rapidly float new carriers

Beginning the war with only seven aircraft carriers in December 1941, the U.S. inventory was reduced to three by years end in 1942. The USS Independence was an expedient of war, having begun its life as the Cleveland Class Light Cruiser – USS Amsterdam (CVL-59), still under construction, almost to her main deck. Development and construction of the then new large sophisticated Essex class carriers, was projected to take far too long to build. The nation was in dire need to rapidly float new carriers

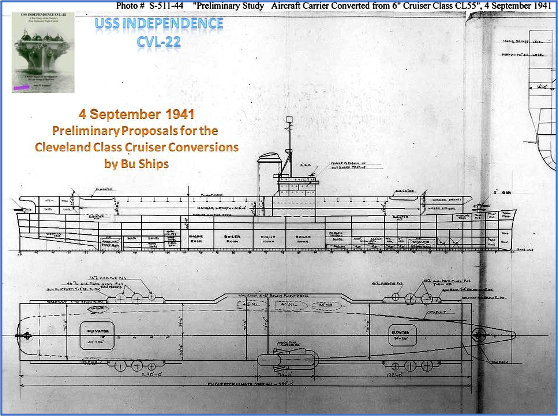

Photo Left: One of the BU Ships initial proposals.

Note the size and placement of the elevators. Also note the single stack positioned with the island, both 50% cantilevered off the flight deck, still interfering with deck space.

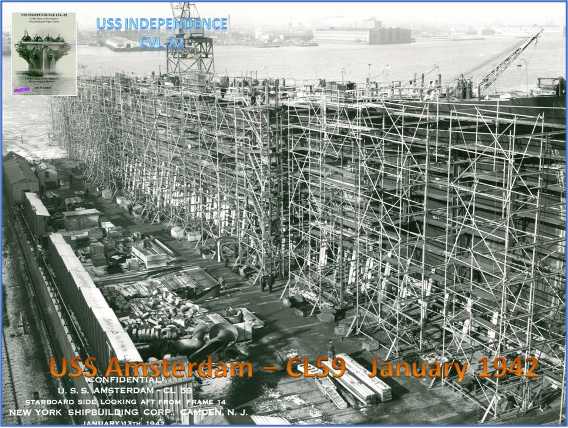

The USS Amsterdam construction began her life in 1941 at the New York Ship Building Yard (NYSB) in Camden, New Jersey. Authorization for the conversion was issued in a Bu Ships letter dated 10 January 1942, to the USS Independence (CV-22 later in 1943 to have her entire class re-designated CVL). Changes were made to the construction to accommodate a flight deck with the removal of the cruiser guns, redesign of the radar system and smoke-stacks, which were cantilevered fully off the flight deck, as well the island. These modifications removed any obstruction to the flight deck to accompany flight operations. The USS Independence (CVL-22) was the lead ship in the Independence Class of light aircraft carriers and was part of a nine-ship inventory that were all commissioned at NYSB in 1943.

The USS Amsterdam construction began her life in 1941 at the New York Ship Building Yard (NYSB) in Camden, New Jersey. Authorization for the conversion was issued in a Bu Ships letter dated 10 January 1942, to the USS Independence (CV-22 later in 1943 to have her entire class re-designated CVL). Changes were made to the construction to accommodate a flight deck with the removal of the cruiser guns, redesign of the radar system and smoke-stacks, which were cantilevered fully off the flight deck, as well the island. These modifications removed any obstruction to the flight deck to accompany flight operations. The USS Independence (CVL-22) was the lead ship in the Independence Class of light aircraft carriers and was part of a nine-ship inventory that were all commissioned at NYSB in 1943.

Photo Left: USS Independence (still labeled USS Amsterdam on the photo caption) well under construction to her main deck, at the time of the orders to stop work and begin the conversion. Note the Philadelphia Navy Yard across the Delaware River where her outfitting by the Navy would assist NYSB in final completion.

Photo Left: USS Independence (still labeled USS Amsterdam on the photo caption) well under construction to her main deck, at the time of the orders to stop work and begin the conversion. Note the Philadelphia Navy Yard across the Delaware River where her outfitting by the Navy would assist NYSB in final completion.

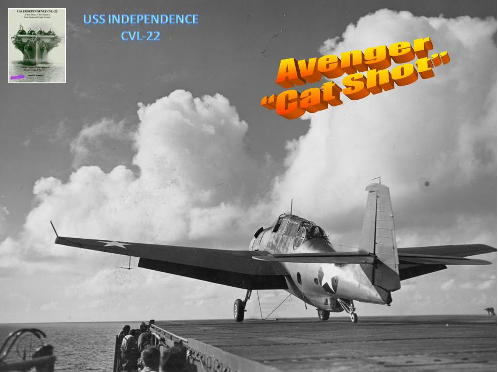

Once launched, the USS Independence was prepared for action. The first air group to deploy was the US Navy Carrier Air Group – Twenty-Two, among the first to receive the new Grumman TBF “Avenger” aircraft.

With a flight deck average width of approximately 73 feet and length of 552 feet (not extending to the bow), it would challenge the skill of her aviators to recover. Aircraft that served aboard her were the: TBF “Avenger” (later General Motors TBM), Douglas SBD “Dauntless”, the Grumman F4F “Wildcat” and later the new Grumman F6F-3 “Hellcat

The carrier, when launched, had a single catapult on the port side of the ship. A bridle was attached to the hooks on each side of the airframe down to a shuttle on the flight deck to prepare an aircraft for the launch. The catapult system was hydraulic-pneumatic with a 10:1 ratio. The hydraulic rams would move approximately eight feet with the cables pulling the shuttle on the deck, moving approximately 80 feet. An air compressor pressurized the fluid in the hydraulic rams to operate the launch mechanism.

Photo Left: This “Avenger” is just airborne with all tires barely clear of the flight deck.

Photo Left: This “Avenger” is just airborne with all tires barely clear of the flight deck.

In this photo the bridle is wrapped around the catapult shuttle and still hooked to the aircraft, about to fall away as the launch nears completion..

The Independence, being a new carrier design, and having limited hangar bay and flight deck space, would need to sort out the proper mix of aircraft on her “shakedown” cruise. With wings that would not fold, it was quickly determined that the Douglas SBD “Dauntless” was unsuitable on the CVL. Additionally, the early “Wildcat” was replaced by the new “Hellcat”. She would go to war with the F6F and TBF / TBM.

The first raid that the USS Independence participated in was Marcus Island in August 1943, just over 1000 miles from Japan. It was a training raid to learn the idiosyncrasies of the still new Independence and Essex Class aircraft carriers, and their most effective use operationally in combat Task Units. There were typically 24 “Hellcats” and 9 “Avengers” that made up the inventory on-board the ship. The Marcus raid was the first raids utilizing the new Grumman F6F Hellcat in combat against the Japanese.

Among the squadrons with Air Group 22 flying from the Independence on the Marcus Island raid were 3 divisions* of Fighter Squadron (VF) Six. The squadron was led by ‘Medal of Honor’ recipient Lieutenant Commander Edward H. “Butch” O’Hare and his wingman, Lieutenant (jg) Alex Vraciu. A second training raid which included the Independence occurred, attacking Japanese held Wake Island. *( Div. = 4 A/C , 2 sections of 2 )

During the Wake Island raid, VF-6, Section Two was flown by Lt(jg) Sy Elton “Sy” Mendenhall and Ens. Allie Willis “Willie” Callan. Our speaker related a story told by both pilots in separate interviews with our speaker. During the course of an engagement with the enemy, both pilots were flying through cloudy conditions and upon exiting a cloud, Ens. Callan fired on an aircraft when he observed a “meatball” *2 on the wing of the opposing aircraft. Subsequent observance revealed it was Callan’s wingman, Lt(jg) Mendenhall. Both landed safely, though Mendenhall was not happy with the event and Callan was embarrassed. *2 (The national Insignia was being changed. The star & blue circle field had primer paint covering the entire circle on Sy’s fighter, looking like a Japanese Insignia under changing lighting in combat maneuvering …. see photo below)

Photo Left: Grumman F6F “Hellcat”

Photo Left: Grumman F6F “Hellcat”

The interviews with both pilots also revealed the quality of leadership exhibited by Lieutenant Commander O’Hare. When speaking with both pilots, O’Hare remarked to Ens. Callan: ” See Willie…. I told you that you were NOT leading your targets enough!” (otherwise his wingman would not have been standing there)

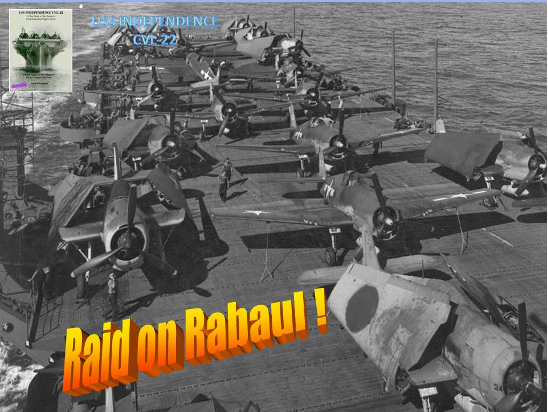

Following the Wake Island mission, the Independence returned to Pearl Harbor for repair and resupply in preparation for the attack on Tarawa. Prior to this attack, the Independence participated in the raid on Rabaul.

Photo Left: This photo shows the aircraft aboard Independence in process of adopting the new National Insignia. The location was also being moved to the other wing.

Photo Left: This photo shows the aircraft aboard Independence in process of adopting the new National Insignia. The location was also being moved to the other wing.

Note the wing on the lower A/C, has the insignia still in primer prior to repaint, while the A/C center aft of it has the old insignia still on the starboard wing (not yet painted out) and the new Insignia (with bars added) freshly painted on the port wing.

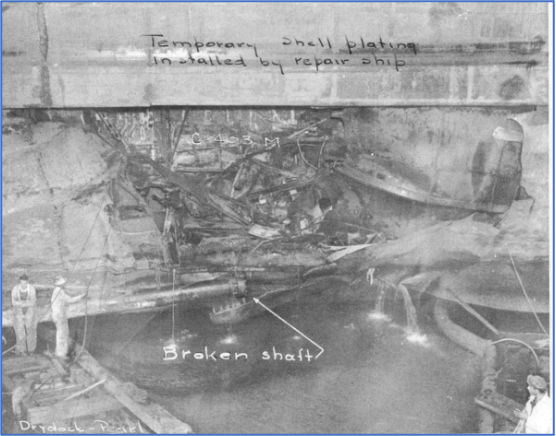

Following the engagement at Rabaul, Independence went to refuel at Espiritu Santo Island and headed for the Gilbert Islands for strikes supporting the Tarawa Invasion. On November 20, 1943, the Japanese counterattacked the American carriers. Independence was targeted by a group of 16 Japanese “Betty” torpedo bombers low to the water. Although six planes were shot down, one of their torpedoes managed to score a direct hit on the ship’s starboard quarter, causing serious damage. A second torpedo struck the carrier but failed to explode. The attack resulted in severe damage and loss of 17 crew members.

Photo Left: Torpedo damage. Three propeller shafts were damaged and the Independence returned to Hunters Point for repairs via Funafuti and Pearl Harbor on one screw.

Photo Left: Torpedo damage. Three propeller shafts were damaged and the Independence returned to Hunters Point for repairs via Funafuti and Pearl Harbor on one screw.

The Independence sailed to the island of Funafuti for temporary repairs (by repair ship USS Vestal) and eventually sailed back to the states in San Francisco for major repairs. A second parallel catapult was added during the repair and additional upgrades including new radar and a new camouflage paint scheme was done prior to her return to combat.

Upon return to full service, the USS Independence was designated as the first dedicated night fighter aircraft carrier. The radar equipped Air Group assigned for this mission was CVLG(N)-41 consisting of night fighter squadron VF(N)-41, flying the F6F-5N “Hellcat” and night torpedo squadron VT(N)-41 flying the “Avenger”. Typical night missions included reconnaissance, combat air patrol and heckling (ground attack). The group was called the “Shademaids”, operating nocturnally under the “shade” or cover of night.

The USS Independence went through three typhoons, including “Typhoon Cobra” where three Fletcher class destroyers were lost. One storm resulted in significant damage to 12 aircraft, 11 in the hangar bay and one lost off the flight-deck. The aircraft were lost due to tie down failures. The ropes would break and the aircraft would move, striking one another, which resulted in damage to the aircraft.

Subsequent night fighter missions of Independence included Eniwetok and the Palaus operation. When no enemy counter-attack appeared during night operations the Independence returned to daylight operations in the Philippines. This was part of Task Force 38.

The Independence participated in operations off Indochina coast. She then supported operations against enemy forces on Okinawa, Formosa and then back to the Philippines. Independence provided both daylight and night operations against the Philippines. By war’s end, the Independence was part of the final carrier strikes against Japan.

Photo Left: Independence during her shakedown to Trinidad. Aircraft aft & port side center are SBDs. TBFs & F4Fs are near the stacks and forward on the flight deck.

Photo Left: Independence during her shakedown to Trinidad. Aircraft aft & port side center are SBDs. TBFs & F4Fs are near the stacks and forward on the flight deck.

At the end of the war, upon return to the U.S. mainland on October 19, 1945, she sailed up the Columbia River to Portland and was the largest ship to sail up the Columbia at that time.

Independence joined the “Magic Carpet” fleet that began on November 15, 1945, transporting veterans back to the United States (with racks in her hangar bay for the troops) until arriving at San Francisco once more on January 28, 1946.

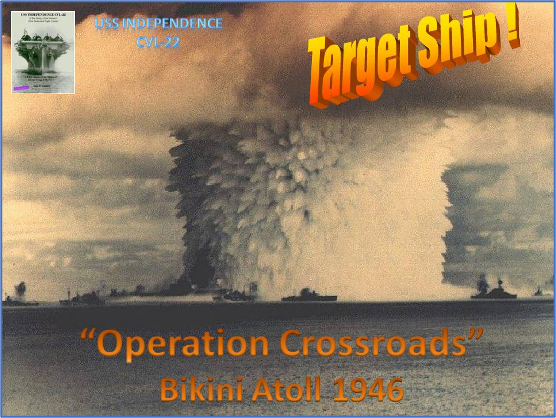

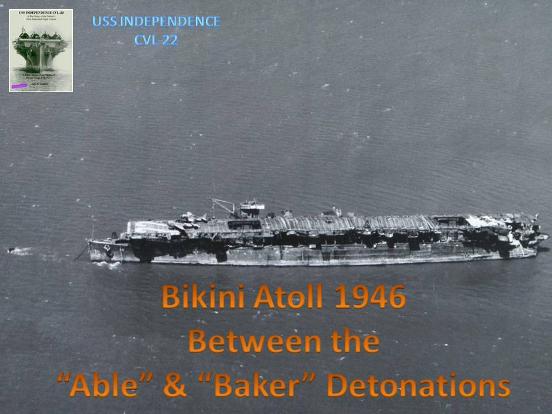

Independence was then ordered to prepare for “Operation Crossroads”. Assigned as a target vessel for the Bikini atomic bomb tests on the fleet, she was placed within one-half-mile of ground zero for the July 1, 1946 “Able” explosion. One large conventional bomb was dropped (an air burst) to test cameras and instruments. The second bomb dropped (also an air burst) was the “Able Test” atomic bomb. The veteran ship did not sink, though her funnels and island were crumpled by the blast. The elevators were blown out and never found. Additional damage to the flight deck and external structure also occurred.

Photo Left: After the “Able” blast, note the two crew members standing on the stern fantail of the Independence.

Photo Left: After the “Able” blast, note the two crew members standing on the stern fantail of the Independence.

After the “Able” test, research teams boarded the ship to inspect the structure, remove testing equipment and make an assessment of the damage. They would also prepare the ship for the second atomic bomb test … “Baker”. “Baker” was an under-water explosion with a device hanging from a cable. The detonation created a bubble of super- heated steam, which exposed the ship to far more radiation then previously experienced from the air burst.

After the “Able” test, research teams boarded the ship to inspect the structure, remove testing equipment and make an assessment of the damage. They would also prepare the ship for the second atomic bomb test … “Baker”. “Baker” was an under-water explosion with a device hanging from a cable. The detonation created a bubble of super- heated steam, which exposed the ship to far more radiation then previously experienced from the air burst.

Following another explosion on July 25, 1946, the ship was taken to Kwajalein and decommissioned on August 28, 1946. Independence, now radioactive was later taken to Pearl Harbor, then east to San Francisco for further studies. The “Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory” (NRDL), newly established at Hunter’s Point near San Francisco, was a new military lab created to study the effects of radiation and nuclear weapons on the fleet. The location was selected for testing due to its proximity to Stanford and the Berkeley Radiation Lab.

The ship was to be studied to determine methods for de-contamination. in addition to the radiation exposure from the bomb tests, portions of the ship were re-contaminated to aid in the studies for de-contamination.

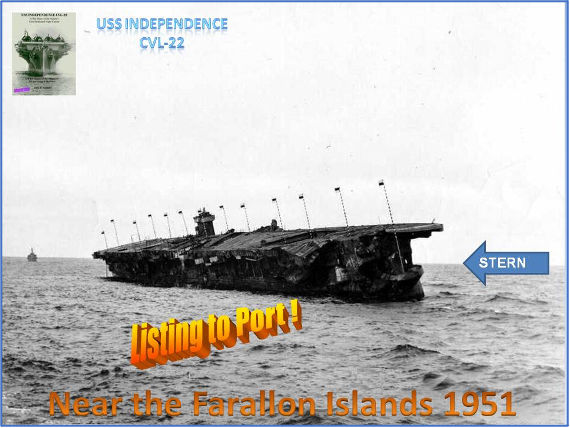

With studies completed at the NRDL, disposition of the Independence was debated. She still had levels of radioactivity, and the value of scrap was depressed. Instead of scrapping her, the ship was loaded up with radioactive waste and towed off the Farallon Islands in January 1951. Final steps in sinking the Independence involved the utilization of new torpedo charges that were placed on the hull to study the impact of the detonations from these new devices on the vessel. The ship was prepared with a series of flags along the flight deck (to help determine blast effects) and was filmed as it sunk. Twenty minutes after the charges went off, the ship disappeared from view. The EX-USS Independence (CVL-22) sank below the waters of the Pacific and her final resting place was some 2700 feet on the ocean bottom.

Photo Left: Charges being placed for the scuttling.

Photo Left: Charges being placed for the scuttling.

Photo Left: After the charges were set off.

Photo Left: After the charges were set off.

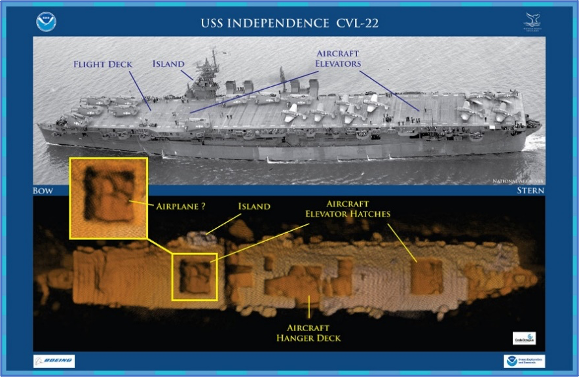

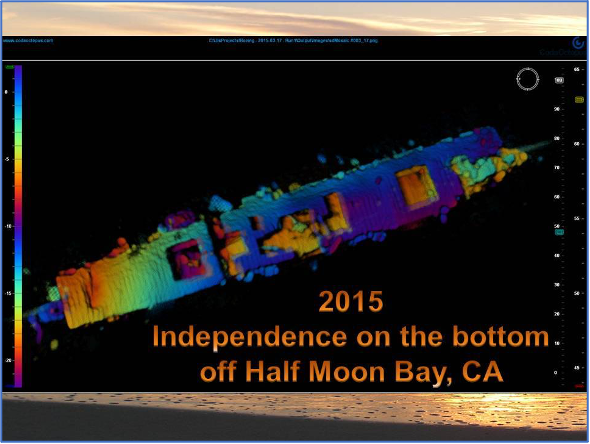

In 2015 a joint mission was created by NOAA (Maritime Heritage Program), the US Navy, Boeing Unmanned Undersea Systems, and a Florida company called Coda Octopus. Coda Octopus is a company that developed an underwater 3D side scan sonar instrument. The 3D side-scan sonar was used to generate distinctive 3D images of the USS Independence. This was mounted on a Boeing marine autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) called the “Echo Ranger“.

The purpose of the mission was to relocate the vessel (last seen in 1951), identify it as most likely the Independence and try to ascertain the condition of the wreck. This would set the stage for the mission the following year in 2016 with the “Nautilus“, Dr. Robert Ballard’s research vessel to provide four days of remote live-stream video and perform a photo survey of the wreck, having positively identifying her as the Independence.

Credit: NOAA, Boeing, and Coda Octopus

Photo Left: 3D side scan sonar image of the Independence from the 2015 mission.

Credit: Boeing

Photo Left: 3D side scan sonar image of the Independence

Photos provided by John G. Lambert (used in his presentation) from his photo and document archive collection on the USS Independence CVL-22.