At their June 2024 meeting, the Grampaw Pettibone Squadron were privileged to have author Steve Snyder share his research and data collection about his father Howard Snyder, who had served as a B-17 pilot in World War II. In his book “Shot Down”, written in 2015, Steve wrote about his father’s experience when he served in the 8th Air Force, 306th Bomb Group.

The book “Shot Down” captures the history of Howard Snyder from enlistment to training then to becoming a pilot of a B-17. It also is a record of the events that occurred when Howard Snyder was shot down and avoided being captured during a mission in World War II. To aide his research Steve became a member of the 306th Bomb Group Association, and served on the Board of Directors. He was also Past President of the 8th Air Force Historical Society.

Howard Snyder was a B-17 pilot stationed in England and in command of a plane called the Susan Ruth, named for his one-year-old daughter. In February 1944, Howard was in command of the Susan Ruth on a mission, when his plane was shot down and he and his crew were reported missing in action.

Our speaker did not have the opportunity to research the events of his father’s experience as an MIA until he retired in 2009. His parents kept many artifacts from the war, and Steve used them in writing his book. Two items that stood out were the letters that Howard wrote to his wife during his time stationed overseas and a diary that Howard kept during his seven months he was MIA. Both were great sources of information.

In addition, Steve contacted family members of the crew his father had served with during his time flying with the 306th. He also researched and compiled many declassified documents associated with the plane, the unit and the mission. Steve’s initial research was a quest to find out more information about his father’s military experience. Over time he realized his research was compelling enough to be the basis for a book and the decision was made to move in that direction.

The first few chapters of “Shot Down”, touch on Howard Snyder’s early years growing up during the depression, his U.S. Army enlistment in early 1941 and marriage mid-1941. Following the U.S. entry into World War II and with the need to support a growing family, Howard Snyder volunteered for pilot training in the spring of 1942. The rest of the book details his flight training, crew selection and the experience of early combat missions, followed by mission problems, details of the mission where Howard was shot down and the events that occurred during his MIA moments in occupied Belgium and France.

The book concludes with the eventual return to allied territory and the travel back home. Steve’s recollection of his journey with his father, led to the writing of the book. The book is an historical accounting of each crew member of the Susan Ruth and the civilians in Belgium who helped during his period in hiding.

The book would not have been written had Steve not met two members of the Belgium community where his father had been protected. Both gentlemen provided detailed records of the events surrounding the loss of the Susan Ruth and were invaluable in providing documentation regarding the period of Howard Snyder’s MIA moments.

The book would not have been written had Steve not met two members of the Belgium community where his father had been protected. Both gentlemen provided detailed records of the events surrounding the loss of the Susan Ruth and were invaluable in providing documentation regarding the period of Howard Snyder’s MIA moments.

Howard Snyder began pre-flight training in June 1942. As he progressed through the various stages of flight training, his height of 6’ 3”, limited his choices in advanced training and final aircraft selection. Basic training began with the Boeing Stearman PT-13 aircraft and progressed to the Vultee BT-13 aircraft. When he elected multi-engine aircraft due to the physical limits in the cockpit of a single engine aircraft, he completed his advanced training in a Curtiss-Wright AT-9, multi-engine trainer. He graduated from pilot training in April 1943 and was commissioned a Second Lieutenant.

Following pilot training, Howard completed transitional crew training and was introduced to the Boeing B-17. Following aircraft familiarization, he was introduced to the crew he was to join before moving to an operational base.

Second Lieutenant Howard Snyder reported to the 306th Bomb Group on October 21, 1943 in Thurleigh, England. The record for the 306th, made it the longest serving bomb group in the 8th Air Force and the first to lead daylight bombing missions over Germany beginning January 27, 1943.

As a result of high casualty figures, the 306th Bomb Group and Eight Air Force faced severe morale problems. These factors became the basis of changes to the command structure with the 306th. The relief of Colonel Charles Overacker is used partly as the model for the motion picture Twelve O’Clock High which was produced between April-July 1949.

Major General Ira Eaker, who commanded the 8th Air Force in England, relieved Colonel Charles Overacker of command of the 306th Bomb Group at Thurleigh and replaced him with Colonel Frank Armstrong. General Eaker had become concerned with the 306th mission performance, along with the growing morale problems brought on by heavy losses.

When the U.S. entered World War II, flight crews were then required to fly until they died, crashed, became a prisoner of war (POW), were wounded, injured, medically removed from flying status, or WWII came to an end. By the early weeks of 1943, the 306th had lost nearly 80% of its original combat crews. In March 1943, Major (Maj.) Thurman Shuller, flight surgeon for the 306th, wrote a letter to General Ira Eaker, 8th USAAF Commander, and requested a limit of 20 combat missions to be established after which a flyer would be relieved of flying duties. The response to his letter did establish a limit of 25 missions.

The 306th Bomb Group were comprised of four bomb squadrons. They were the 367th, 368th, 369th and 423rd.

Howard Snyder was assigned to the 369th, nicknamed the ‘Fightin Bitin’. The 306th were equipped with the B-17 bomber, designed and built by the Boeing company. While Boeing built 60% of the aircraft, Lockheed Vega and the Douglas company produced the remaining 40%. Over 12,700 were produced in different versions. Only three variations, the E, F and G model served in any significant combat role. The most recognized version, the G model can be identified by the two machine guns mounted under the nose of the plane and referred to as the chin turret.

The aircraft has a ten-man crew, four officers and six enlisted personnel. The officers are the pilot, co-pilot, bombardier and navigator. The enlisted personnel are the crew chief/flight engineer, radio operator, waist gunners, ball turret gunner and tail gunner. Prior to arriving over the target, the bombardier also operates the chin turret, while the navigator is responsible for the multiple cheek guns in the nose of the plane. The flight engineer is responsible for the top turret and the radio operator on some models has a machine gun mounted above his seat just aft of the bomb bay.

The two waist gunners standing on either side of the aircraft in the main body are the most exposed and responsible for defending the plane on missions. The ball turret gunner who remains in the turret during most missions, protects the aircraft while sitting in a very confined fetal position. The tail gunner, also in a very confined space, protects the plane whenever attacks from behind the plane are launched by enemy aircraft.

Back row: L to R: Flight Engineer/Top Turret Gunner Roy Holbert, Ball Turret Gunner Louis Colwart, Radio Operator Ross Kahler, Right Waist Gunner John Pindroch, Left Waist Gunner Joe Musial, & Tail Gunner William Slenker Front Row Kneeling: L to R: Pilot Howard Snyder, Co-pilot George Eike, Navigator Robert Benninger & Bombardier Richard Daniels

On February 8, 1944 the Susan Ruth was on a mission to Frankfurt, Germany. The crew that day were: pilot-Howard Snyder, co-pilot-George W. Eike, bombardier-Richard Daniels, navigator-Robert Benninger, flight engineer/top turret gunner-Roy Holbert, radio operator-Ross Kahler, right waist gunner-John Pindroch, left waist gunner-Joe Musial, ball turret gunner-Louis Colwart and tail gunner-William Slenker. The Susan Ruth was successful in dropping their bombs on the target. However, after turning off the target to return to their base, heavy flak bursts hit in the left wing, sustaining serious damage to the aircraft belly. The bomb bay doors could not be closed due to the battle damage which slowed the plane and required higher fuel usage to remain at the same air speed and altitude. The plane began falling back from the group and as they left German airspace and entered French airspace, they were attacked by two German fighters, FW190s.

During the air battle, the Susan Ruth was shot down. Two crew members, ball turret gunner-Louis Colwart and radio operator-Ross Kahler, were killed during the attack. The remaining eight members bailed out successfully. Bombardier-Richard Daniels, Waist gunner -Joe Musial and top turret gunner/flight engineer-Roy Holbert were captured, but survived the war. The remaining Susan Ruth crew were initially helped by the resistance and hidden. Both attacking fighters were shot down and one pilot was killed, while the second pilot survived the war.

Howard was the last crew member to bail out and came down along the French and Belgium border. Two Belgium citizens came upon the pilot hanging by his parachute in a tree and helped him down. This occurred in the early afternoon and the two men instructed him to go into hiding until later at night when they would return to lead him to a more secure hiding place. He was taken to a farm house in Belgium across the border from where he came down. The next night, a Belgium customs officer, a member of the underground assisted in relocating Howard to another house. Directed by other Belgium citizens, Howard was moved from one location to another depending on the presence of the German patrols in the area.

Since Howard did not speak the local language, he avoided being seen in public and continued to be moved from one location to another.

While staying with one family, a German patrol came to the location and Howard was sent out of the apartment and told to go up on the roof and hide. With the German patrol remaining in the area throughout the night, Howard was forced to remain on the roof all night. This posed a challenge since the tiled roof was very steep.

While staying with one family, a German patrol came to the location and Howard was sent out of the apartment and told to go up on the roof and hide. With the German patrol remaining in the area throughout the night, Howard was forced to remain on the roof all night. This posed a challenge since the tiled roof was very steep.

Even while being protected by members of the underground, Howard was unable to contact American forces, and did not know the status of any of his flight crew from the time his plane was shot down. He referred to an English-French phrase book in his escape kit, in order to communicate with those in the local community helping him.

The citizens in the area exhibited many acts of bravery. Hiding and protecting many allied flyers and soldiers put many at risk. Even after exposing themselves and their families to the potential of being captured, tortured or killed by the enemy, they still risked their lives and that of their family.

Upon learning that the Americans had landed on the Normandy beaches, Howard wanted to get back into the fight. With his previous training in the infantry, he knew how to fight on the ground. In spite of the people trying to convince him not to go, Howard wanted to be introduced to the French resistance. He crossed the border to France to meet members of the French resistance, the Maquis.

Howard joined the Maquis and participated in numerous operations against enemy forces. Seven months after bailing out of his B-17, Howard became aware of American forces in a nearby village, Trelon, France. He entered the village, approached a U.S. Army Major and identified himself. After being interrogated and having his story corroborated, he was transported to Paris, France and flew back to England on a US transport. He contacted his mother to let her know he was okay after being missing for seven months.

Howard returned to the U.S. and became a B-17 instructor. The military rules prevented personnel from returning to combat in the region where they were shot down and helped by the local citizens. A concern for subsequent combat and possible capture and interrogation could reveal the organization that existed in the local area, including the resistance.

The five members of the Susan Ruth crew that bailed out and were initially helped by the local population friendly to allied forces did not all survive the war. Pilot-Howard Snyder and tail gunner-William Slenker were saved by members of the resistance and made it back home. Co-pilot-George W. Eike, navigator-Robert Benninger and waist gunner-John Pindroch were hidden by the resistance but collaborators reported the resistance to the German authorities. All three crew members along with locals were captured, tortured and executed by the German military.

Our speaker pointed out that most of the people of Belgium are wonderful people. He commented that “to this day, they are so grateful to the Americans that liberated them from four years of Nazi occupation and Nazi oppression.” They do a great job of educating the younger generations to remind them as well of the contribution made by those who rescued their country. They built a number of memorials to remember the help provided by many. On September 2nd of each year, they hold a major celebration to recognize the liberation of the country from Nazi control.

Our speaker pointed out that most of the people of Belgium are wonderful people. He commented that “to this day, they are so grateful to the Americans that liberated them from four years of Nazi occupation and Nazi oppression.” They do a great job of educating the younger generations to remind them as well of the contribution made by those who rescued their country. They built a number of memorials to remember the help provided by many. On September 2nd of each year, they hold a major celebration to recognize the liberation of the country from Nazi control.

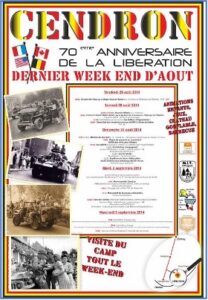

Ceremonies take place at numerous memorials. One event took place at Cendron that celebrates the spot where the U.S. 9th Infantry crossed over the Wartoise River from France into Belgium on September 2, 1944 to liberate the country. All the people in the local villages attend. Dignitaries make speeches. Military units from the U.S. Air Force, Belgium and France are represented. Young members of the community not only participate, they are out in front to remind all of the need to remember as well as to emphasize the need for vigilance.

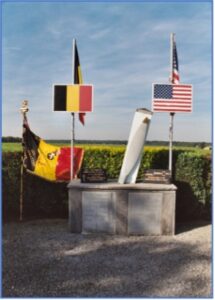

The above picture is the memorial to the crew of the B-17 Susan Ruth which was erected in 1989 at Macquenoise, about two hundred yards from where the plane came down. The plaque on the front lists the names of the crew, their positions in the plane, and their age at the time they were shot down. Howard, along with the three other crew members who were still living at the time attended the dedication.

Like most World War II veterans, Howard did not talk a lot about the war. However, being reunited with many of the Belgium and French citizens and seeing all the places where he stayed brought it all back and he began to talk about it after that visit. Steve’s first trip to Belgium was five years later in 1994, when he accompanied his parents, with his wife and sister to attend the 50th Anniversary Celebrations of the liberation of the region. That is when it became personal to Steve and he saw everything firsthand.

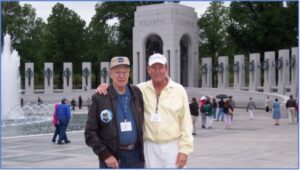

Howard and his son visited the World War II Memorial in Washington, DC in 2004. They also attended a reunion of the Air Forces Escape & Evasion Society. This was the last trip Howard ever took. He died three years later in 2007. Howard wasn’t the last Susan Ruth crew member to die, but he was the oldest at 91.

The Grampaw Pettibone Squadron of the ANA, would like to thank Steve Snyder for sharing his book and his thoughts about his father’s story.

IT’S OUR DUTY TO REMEMBER

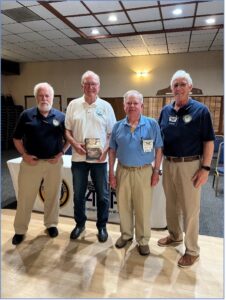

L to R: David Malmad-GPS PAO, Steve Snyder -Speaker, Vince van der Brink- GPS staff, Tim Brown – GPS President