Speaker: Marc Liebman, Captain USN (ret)

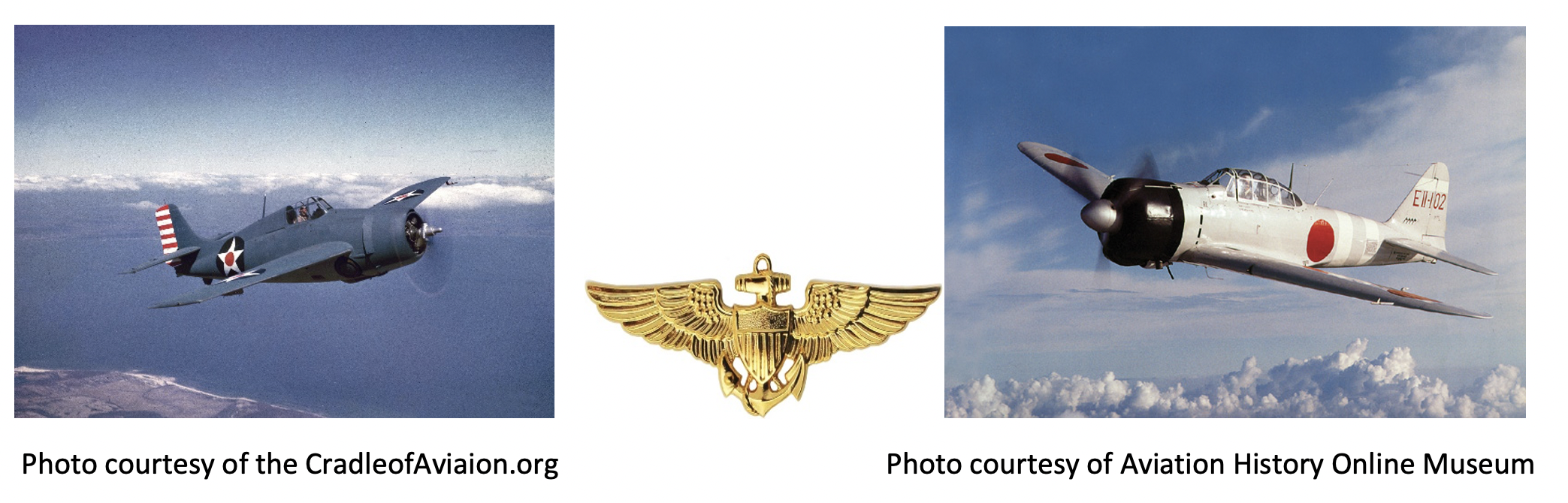

At their March 11, 2021 zoom meeting, Grampaw Pettibone Squadron and Two Block Fox Squadron hosted a presentation by Marc Liebman, Captain USN (ret). Marc has shared his experience as a Naval Aviator, author and historian. In his presentation, Marc compared the Grumman F4F Wildcat with the Mitsubishi A6M Zero-Sen. His research began when a comment made to him at an air show by one of the performers, stated that the Wildcat is grossly underestimated as a fighter. Based on the comment and subsequent research, the following presentation was developed.

The Grumman Wildcat was first proposed as a biplane in March 1936. The Navy requested a monoplane version in the summer of 1936 and the finished aircraft designated XF4F-1 competed against the Brewster Buffalo, XF2A-1 in June 1938, as the newest carrier fighter. The Buffalo won the competition. The Navy purchased the F2A, but it also acquired 40 Grumman F4F-3s. The F2A began to experience operational issues, beginning with the landing gear function and aircraft performance as more weight was added to the aircraft. Eventually, the Navy Brewster Buffalos were replaced by the Grumman F4F-3.

Early production volume of the Wildcat went to foreign military orders which surpassed US Navy purchases. Aircraft orders were received from the British, French and Greeks. The French and Greek orders, however were subsequently sold to Great Britain when Germany occupied both countries. The first confirmed combat success was scored when an RAF plane downed a German Junkers Ju 88 bomber over Scapa Flow on December 25, 1940. The first US Navy Wildcats, the F4F-3, did not fly until April 1941.

Three basic models of the F4F are presented in the following chart.

| Category | F4F-3 | F4F-4 | FM-1/2 |

| Fleet Air Arm Designation | Martlet I and II | Martlet II/IV,

Wildcat IV |

Martlet VI

Wildcat VI |

| Engine | P&W 14-cylinder, two row R-1830-86 | P&W 14-cylinder, two row R-1830-86 | Wright 9-cylinder, single row R-1820-56 |

| Armament | 4 M2 .50 Caliber machine guns with 430 rpg | 6 M2 .50 Caliber machine guns with 240 rpg | 4 M2 .50 Caliber machine guns with 430 rpg |

| Service Ceiling | 37,000 feet | 33,700 feet | 35,600 feet |

| Max speed | 331 mph @22,000 | 318 mph @ 19,400 feet | 320 mph @ 28,000 feet |

| Range with external tanks* | 860 miles | 1,275 miles * | 1,350 miles * |

| Wing | Fixed wing | Fixed wing. Modified version had manually folding wing | Folding wing |

Source: Marc Liebman

The design and performance differences between the models are notable. While the basic Dash 3 Wildcat model is faster than the remaining models, it does have a much shorter range. The Dash 4 model carries six .50 caliber machine guns while the other models are equipped with only four guns. With 4437 made, the FM-2 was the most widely produced Wildcat. With a lighter engine, four .50 caliber machine guns and the addition of a folded wing for carrier operations, it was the best performing model. The FM-2 made its first flight at the beginning of 1943. A total of 781 Wildcats were sold to the Royal Navy.

By the end of 1943, the Wildcat was off the fleet carriers and was replaced by the Grumman F6F and later by the Vought F4U Corsair. The F4F was the primary US Navy fighter in the early days of World II. The comparison between the F4F with the Imperial Japanese Navy A6M Zero-Sen and its most qualified pilots, was the basis of the research carried out by the speaker.

In the next part of the presentation, Marc described the Japanese development of a front-line fighter. Beginning in 1937, the Japanese recognized a need to develop a new fighter based on lessons learned in China. A need for a lighter, faster, more maneuverable, better armed and longer range was the objective. The first prototype from Mitsubishi flew in September 1939 and was accepted by the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) in July 1940. The aircraft was identified as the A6M Type Zero-Sen and was an outgrowth from the open cockpit, fixed gear A5M Type 96 aircraft. Both Mitsubishi and Nakajima produced the plane while Nakajima Industries built the engines.

To reduce aircraft weight, the new plane was manufactured with a new light weight aluminum alloy by the Sumitomo Metal Company, called Extra Super Duraluminum. Additional weight reduction features were the absence of self-sealing fuel tanks or armor for the pilot. Further weight reduction was gained by a light-weight engine, and elimination of a radio. Large ailerons optimized performance especially when performing various aerobatic maneuvers between 180 and 250 mph between 10,000 – 15,000 feet.

There were four different models of the aircraft built with Model 21 the most common during the battle for Guadalcanal. A total of 10,938 aircraft of the four models were built.

| Model 21 | Model 22 | Model 32 | Model 52 | |

| Engine | Nakajima Sakae-12, two row, 14-cylinder radial with 1 stage supercharger 850 HP | Nakajima Sakae-21, two row, 14-cylinder radial with 2 stage supercharger 1,130 HP | Nakajima Sakae-21, two row, 14-cylinder radial with 2 stage supercharger 1,130 HP | Nakajima Sakae-21, two row, 14-cylinder radial with 2 stage supercharger 1,130 HP |

| Armament | Two 7.7mm machine guns @ 680 rpg + two 20 mm cannon with 60 rpg | Two 7.7mm machine guns @ 680 rpg +

two 20 mm cannon with 100 rpg |

Two 7.7mm

machine guns @ 680 rpg + two 20 mm cannon with 100 rpg |

Two 7.7mm machine guns @ 680 rpg +

two 20 mm cannon with 125 rpg |

| Service Ceiling | 33,000 feet | 33,000 feet | 30,000 feet | 35,100 feet |

| Max speed | 331 mph

@14,900 feet |

388 mph

@ 19,690 feet |

341 mph

@20,500 feet |

351 mph

@20,000 feet |

| Range with external tanks | 1,400 miles | 1,400 miles | 1,200 miles | 1,400 miles |

| Wing | Tips folded | Tips folded | Folding tips removed | Folding tips removed |

Source: Marc Liebman

The Zero was fully operational before the Wildcat appeared. When first encountering the Zero, British pilots flying the Sea Hurricanes over Ceylon were out flown when trying to use traditional dog fighting tactics and engage in a turning fight.

In the Wildcat’s first clashes with the Zero after Perl Harbor during carrier raids in early 1942 and the Battle of the Coral Sea, the kill ratio between the Zero and Wildcat was estimated at 1.5/1. Using lessons learned from these early encounters along with intelligence from the American Volunteer Group, James Flatley and Jimmy Thach, tactics were developed to counter the Zero’s advantages.

During the Battle of Midway, the squadron’s that used Thatch’s and Flatley’s tactics had success. The Navy and Marine Corps pilots based on Guadalcanal used the airplane’s higher roll rate, ability to dive and the availability and use of an early warning system to their advantage when Japanese aircraft were coming. By the end of the Guadalcanal campaign in February 1943, the Wildcat was shooting down 5.9 Zeros for every Wildcat that was lost.

A crashed Zero was captured in Alaska in July 1942, and then brought to the U.S. and repaired. By September 1942, after fully evaluating the Zero, tactics for Navy and Marine Corps aviators flying the Wildcat were refined. By the end of the war, the Wildcat vs. Zero kill ratio had climbed to 6.9/1.

Marc reviewed the statistics of both aircraft asking, why the kill ratio increased so dramatically. When comparing the F4F-4 or the FM-2 variation, the following factors are noted:

- With only 60 rounds per cannon, the Zero had about 10 seconds of ammunition for its 20mm cannon.

- The light construction meant that the Zero airframe could not absorb any punishment and coupled with lack of self-sealing fuel tanks and pilot armor, the Zero would easily catch on fire and/or the pilot incapacitated when hit with a burst from a Wildcat’s .50 caliber machine guns.

- The Zero had a traditional float type carburetor that would starve the Zero’s engine of fuel if the airplane was flown inverted with less than 1g or if negative Gs were incurred if the nose was pushed over rapidly to dive after a Wildcat.

- Without a radio Zero pilots couldn’t coordinate their attacks or defense of their formations.

- The Wildcat was capable of diving at 400+ mph while the Zero’s controls began to stiffen at 250 mph and by 350 mph Japanese pilots could barely move the control stick or controls.

A table review of the advantages and limits of the F4F-4, Zero and FM-2 are as follows.

| Category | F4F-4 | A6M Model 21 | FM-2 |

| Maximum takeoff weight | 7,964 | 6,025 | |

| Typical Empty Weight | 5,895 | 3,704 | |

| Engine HP (max continuous) | 1,350 | ||

| Supercharger | 2 stage | 1 stage | 2 stage |

| Fuel Feed | Pressurized injection | 2 Barrel Float | Pressurized injection |

| Wing Loading in lbs/sq ft at Max Takeoff Weight (MTOW) | 30.63 | 24.95 | |

| Power to weight ratio at MTOW | 5.5 lbs/hp | ||

| Service Ceiling in feet | 37,000 | ||

| Rate of climb-sustained | 2,190 ft/min | 2,600 ft/min | |

| Ammo Load | 430 rounds per gun | ||

| Rate of Fire | 750-850 rounds/min | 7.7mm mg–500 rounds/min

20mm cannon–520 rounds/min |

750-850 rounds/min |

| Range -internal tanks | 830 miles | 1160 miles | |

| Range -internal + external tanks | 1030 miles | 1400 miles | |

| Armor | Self-sealing tanks, pilot armor seats | None | Self-sealing tanks, pilot armor seats |

| Radio | 9 channel + guard | None | 9 channel + guard |

Source – Marc Liebman

While the Zero was great as an aerobatic aircraft, the minimum protection decreased survivability in combat. The Wildcat was designed as a combat aircraft and was capable of engaging the enemy, and surviving damage while protecting the pilot.

In addition to aircraft design and performance features, the armament for the Zero was found to be problematic. The aircraft was equipped with both 7.7mm machine gun and 20mm cannon. Guns are adjusted to have shots converge at a set distance when the plane is straight and level. The ballistics of the 20mm cannon shell and the 7.7mm bullet are very different. When engaged in a dogfight and maneuvering, most shots are at turning enemy airplanes.

Navy and Marine Wildcat pilots learned to make slashing attacks by utilizing the Wildcat’s ability to maneuver while diving to gain tactical advantage. However, even when aware of the Zero advantage in a turning fight, it simply wasn’t always possible to avoid getting into a turning dogfight with a Zero.

The Thach Weave is an aerial combat tactic developed by naval aviator John S. Thach and named by James H. Flatley of the United States Navy soon after the United States’ entry into World War II. If one Wildcat in a two-plane element was threatened by a Zero, they would both turn toward each other. This enabled one of the airplanes to engage the Zero in a head-on shot. If the Zero turned away, one of the Wildcats could adjust its turn to get on the Zero’s tail.

The Thach Weave

The technique was first tested during the Battle of Midway. However, it was still some time before it was a common practice to use by other pilots in the Navy. According to Marc, it is a technique that was employed by helicopter pilots in Afghanistan to constantly clear their six o’clock position and spot surface-to-air missiles fired at the helicopter.

According to Marc, it was necessary to understand the dynamics of a pursuit between aircraft. When the angle of bank exceeded 60 degrees and the thrust to weight ratio does not exceed 1:1, the aircraft loses speed and lift. Most WWII dogfights were a descending spiral. As the plane slows down, the radius of turn becomes smaller even though the rate of turn remain the same. This causes the angle of each segment and diameter of the circle to become smaller. If Wildcat pilots could slow the speed of the fight, the advantage previously held by the Zero was not as great. This would require the pilot being pursued to dive out of the encounter, while the Zero could either dive or climb. The tactic developed by the US Navy was to dive, shoot and dive.

Toward the end of his presentation, Marc posed a number of questions, accompanied by explanations. Referencing documentation from the Naval History and Heritage Command and other publications, there are three reasons why the Wildcat pilots enjoyed 6.91:1 kill ratio by the end of the war.

The three reasons why the kill ratio favored Wildcat pilots?

- Training

Beginning in the 1930s, the US Navy taught deflection gunnery which enable the pilot to instinctively know where to aim and fly. After the Battle of the Coral Sea, experienced pilots would be rotated into training units and use their combat knowledge and skill to train new pilots in the Replacement Air Group (RAG). This improved the skills at a much earlier stage when new pilots were assigned to combat groups.

While Japanese pilots were more experienced at the beginning of the war with the US, over time the attrition rate reduced skill levels. Pilots flew until they were killed, seriously injured or unable to fly due to illness or disease. Lack of resources and an inflexible- training methodology and philosophy reduced the quality of new pilots or acquisition of improved tactics. Limited production of new aircraft further impacted the ability of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) response.

- Radar, Radios and CIC

The Battle of Midway and the Solomon campaigns saw the use of the Combat Information Center (CIC) develop as a significant operational tool. Other engagements saw the US use of Australian Coast Watchers in the Solomon Islands. This enabled Wildcat and P-39 units to launch with enough advance notice in order to have an altitude advantage when the Japanese formations aircraft arrived on the scene. Radar could identify and direct groups airborne to converge on enemy forces quickly. Individual pilots could communicate by radio and support group response more efficiently. Because Zero pilots didn’t have radios, they could not communicate with each other and could not coordinate their defense of the bombers nor redirect other Zeros to the attacking American planes. By sharing knowledge gained by the RAF from the Battle of Britain on how to efficiently vector fighters to attack enemy formations, US squadrons were able to significantly increase their response to enemy activity.

- Aircraft

American built aircraft were sturdier, had more armor protection for the pilot and fuel tanks designed to minimize the danger from fire. A single burst from a Wildcat’s M2 .50 caliber guns was more than enough to inflict mortal damage to a Zero. On the other hand, once the Zero ran out of 20mm cannon shells, its 7.7mm (.30 caliber) machine guns would do little damage to the Wildcat unless one killed the pilot. The Wildcat pilots had another advantage. Ballistics of the .50 caliber guns were consistent and the pilots did not have to compensate for the different flight paths of the 20mm shells and 7mm bullets. With the ability for the Wildcat to climb to altitude and be vectored to an advantageous position, U.S. Naval and Marine Corps Aviators could dive, shoot and dive away knowing that the Zero pilots would struggle to maneuver their Zeros once the speed increased above 300mph. Beginning in late 1943 when the F4U Corsair and the F6F Hellcat arrived on the scene, the kill ratio in favor increased markedly. By the end of the war the Grumman F6F saw a kill ratio of 19:1, while the Vought F4U had an 11:1 rate.

In closing, Marc noted that while some pundits indicated the Zero was a better aircraft or the Wildcat not as good, they were about the same. How the aircraft was employed, training, tactics and aircraft survivability contributed to the bottom line when the planes met during the war.

Questions

Did the Wildcat serve in the European Theater?

Yes. The first Wildcat kill of World War II was made by a Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm pilot when he shot down a Ju-88 over the Royal Navy base at Scapa Flow on Christmas Day, 1940.

Wildcats flying off the U.S.S. Ranger (CV-4) provided combat air patrol for the invasion of North Africa in November 1942. Naval Aviators flying Wildcats shot down 15 Dewoitine 520s flown by Vichy French pilots and lost only two. Later in October 1943, a joint U.S. Navy/Royal Navy task force sank 31,000 tons of German shipping off Bødo, Norway. The only air-to-air action was after the attack which surprised the Germans occurred as the task force was withdrawing. Two Heinkel 115s and one Ju-88 were shot down.

The last Wildcat kill in the Atlantic was also made by a Fleet Air Arm pilot in April 1945 when Wildcats flying off Royal Navy carriers engaged German fighters off Northern Norway during a raid on a U-Boat base. Three Me-109s were bagged with no loss to the Wildcats

How was the movement of experienced US pilots back to a training command significant.?

US forces gained a significant level of capability from lessons learned when experienced pilots were brought back to help train those right out of the training command. The U.S. Navy quickly applied the lessons learned from each battle to improve the way Naval Aviators were trained for combat. One of the lasting changes was the creation of the Replacement Air Groups (RAGs) that focused on developing skills in a specific type of airplane. In other words, there separate RAGs for Wildcats, another for Hellcats and another for Corsairs. All this helped prepare Navy and Marine Corps Aviators for combat.

This was significantly different than the Japanese who kept their pilots in front line squadrons until they were killed or disabled.